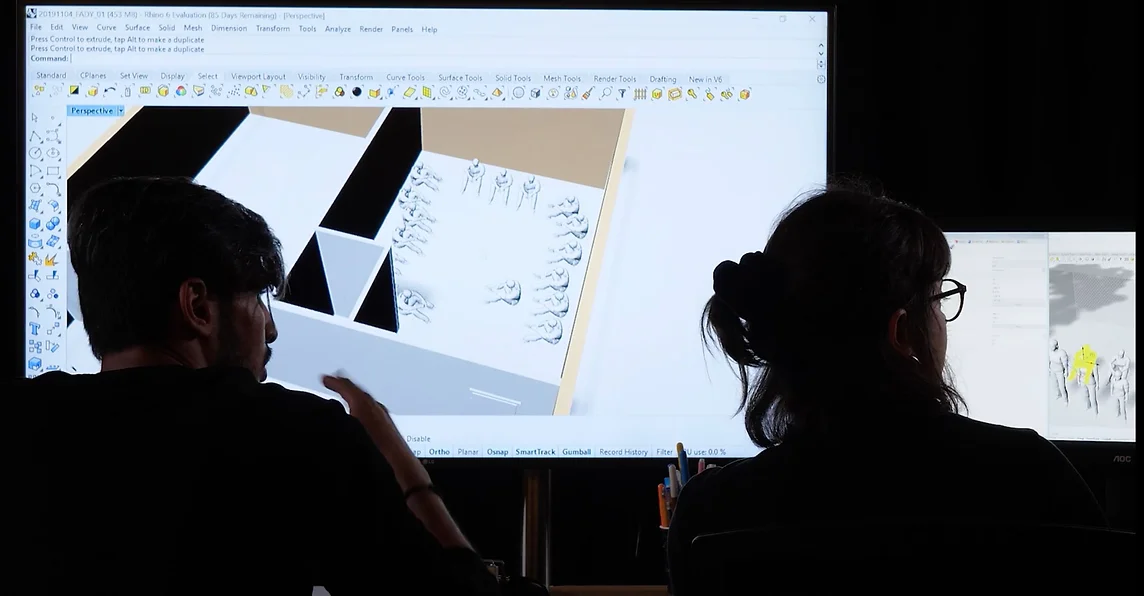

Screenshot from Forensic Architecture’s ‘situated testimony’ (2019)

“I felt like I didn’t exist, that I was nothing.”

FADY, The Intercept

“I want them to know about what happened at the borders with the refugees and immigrants. I want them to know about what the commandos do to them and how they treat them.”

Filed in November 2020, and registered and communicated to Greece in November 2021, this is the first submission to the Human Rights Committee regarding Greece’s systemic policy of collective and summary expulsion of racialised persons at Evros. In 2016, 21-year-old Fady was living in Germany with refugee status when his 11-year-old brother fled Syria to escape ISIS and seek international protection, and disappeared while crossing the Evros River into Greece. When Fady flew to Greece to look for his missing brother, he was racially profiled and abducted by Greek police who illicitly seized his German residency and refugee documents and placed him in incommunicado detention without any official record or paper trail. Greek border forces and commandos in balaclavas forcibly transported him and others in a dinghy across the Evros River, in the presence of German-speaking Frontex officers. Following this ‘pushback’, Fady experienced cardiac arrest, leading to heart surgery and prolonged treatment.

Fady spent an entire year reattempting reentry into Greece, after being denied assistance by the German authorities, who refused to reissue his German identification documents and thereby also denied his recognition and protection by law. Despite holding German residency and EU refugee status, Fady was effectively rendered undocumented for nearly three years, during which he experienced multiple expulsions from Greece (while reattempting reentry 14 times) and was repeatedly exposed to deportation to Syria. His brother remains missing to this day.

FAA v Greece is the first case brought before the UN Human Rights Committee about the racialising state violence of collective summary expulsions, or ‘pushbacks’, from Greece. This is one of a few cases pending before the Committee on ‘pushbacks’ at Europe’s borders. It is the second case, after that brought against Croatia (represented by the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights), to argue that the racist state violence of borders is a form of enforced disappearance.

context

For decades, Greece has been subjecting refugees, asylum-seekers and other migrants to violent summary expulsions across the Evros-Meriç River, which forms the border between Greece and Turkey. When the 2016 EU-Turkey Statement sharply reduced the ability of asylum-seekers to reach Greece by sea, attempted crossings by land increased, and violent expulsions across the Evros River became part of a systematic unofficial policy.

Individuals who are apprehended by Greek officials in the border region are characteristically treated in an inhuman and degrading manner (including through beatings and the seizure of their paperwork and belongings). They subject to incommunicado detention, denied access to procedural remedies, and ultimately violently and clandestinely expelled (‘pushed back’) across the Evros River on rubber boats. This systemic practice of summary and collective expulsions in the Evros border region dates back to at least 2018 and is extensively documented. It has also been repeatedly condemned by the UN and European bodies and international civil society for the long-lasting harms it continues to inflict on thousands of refugees, asylum-seekers and migrants, depriving them of the right to access asylum, and exposing them to life endangering conditions and ‘chain refoulement’ by Turkey.

While this practice intensified since the violent events at the Evros border in March 2020, it remains entirely clandestine and subject to persistent denial by the Greek authorities and government at the highest echelons: it has no institutional paper trail and is often conducted by masked commandos and often involves Frontex personnel.

Despite Greece’s continued systemic breaches of international and EU laws (e.g., the EU asylum acquis and EU Charter of Fundamental Rights), EU institutions, including the European Commission and the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex), have failed to respond to Greece’s unlawful conduct and instead continue to provide Greek border enforcement with significant financial and technical assistance (see European Ombudsman complaint about the Commission’s maladministration of funding for Greece’s pushbacks).

Fady’s case exemplifies both the racism and discrimination that underlies Europe’s border regime and its normalisation of so-called ‘pushbacks’. Fady, who did not arrive from Turkey, was racialised and thus presumed by police to have entered European territory “illegally”.

facts

Fady is a young man from the Syrian city of Deir az-Zour. After ISIS took over his region, Fady found himself in physical danger and proceeded to flee to Germany, where he was granted refugee status in 2015. The following year, Fady’s 11-year-old brother Mhamed also fled Syria to escape ISIS recruitment. In November 2016, Mhamed tried to reach Greece to seek asylum and was last seen after crossing by the Evros River. The 11-year-old then disappeared.

With his German ID and refugee status documents, Fady flew from Germany to Greece to search for his missing little brother. On 30 November 2016, right as he began his search, Fady was singled out by Greek police officers in a bus station and questioned about his national origin. Despite his EU refugee status and German residency permit, once the officers learned he was of Syrian origin, they immediately apprehended him, confiscated his cell phone, and drove him by van to an unknown location.

The officers detained Fady incommunicado in a building where they strip-searched him and confiscated his German residence card and refugee documents, and his house keys. He was beaten and detained for several hours along with roughly 50 others, who were held in overcrowded cells in unsanitary conditions, without access to food, water, medical care or legal assistance. In the middle of the night, the officers transferred Fady and the group into a van and drove them to the Evros River, where armed commandos wearing balaclavas forcibly transferred them across the river on a rubber boat and left them on the Turkish riverbed.

Following this experience, Fady experienced cardiac distress, underwent emergency hospitalisation and heart surgery, and required prolonged treatment.

While stranded in Turkey without his documentation, Fady tried to seek help from the German Embassy but was denied assistance. He attempted to re-enter Greece 14 times over the course of the following year, and was further subjected to repeated ‘pushbacks’ by Greek authorities. He finally was able to enter Greece unofficially and reach Athens in December 2017. He again sought help from the German Embassy, but was forced to wait another two years, during which he remained undocumented in precarious and destitute conditions, until Germany finally reissued his documents and permitted him to travel home to Nuremberg. It was only on 30 October 2019, almost three years on from 30 November 2016 when his documents were clandestinely seized and he was expelled, that he was able to officially return to Germany. During those three years, Fady was effectively rendered stateless.

Fady’s expulsion was reconstructed by Forensic Architecture, who also provided an expert opinion in the case.

legal case

On 17 November 2020, we submitted an ‘individual communication’ of F.A.A. v Greece (CCPR 4038/2021) on behalf of Fady to the UN Human Rights Committee, arguing that Fady’s summary expulsion violated several of Greece’s legal obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Cumulatively, the complaint argues that Fady’s incommunicado detention and clandestine deportation from EU territory removed him from protection of the law in a manner that meets the definitional elements of an act of enforced disappearance.

In this complaint, we argue that Greece’s treatment of Fady violated several of his human rights under the ICCPR, including: the right to life (Article 6); the prohibition of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (Article 7); the right to liberty and security, including the prohibition on arbitrary arrest or detention (Article 9); the right to dignity (Article 10); the freedom to leave a country and right to enter one’s own country (Article 12); the prohibition of collective expulsions (Article 13); the right to recognition as a person before the law (Article 16) and to equality before courts and tribunals and to a fair trial (Article 14); the right to privacy (Article 17); the prohibition of discrimination (Articles 2 and 26); and the right to an effective remedy (Article 2).

The communication argues that the absence of an institutional paper trail in cases of illegal detention and expulsion is a form of active concealment of evidence that bars access to remedies under Greek administrative, civil and criminal laws and procedures, and which makes Greek courts both unwilling and unable to investigate such abuses of power by the Greek state. Coupled with the government’s persistent denial that Greek officials are conducting ‘pushbacks’, these circumstances deny survivors of ‘pushbacks’ and bereaved families like Fady’s in search of information about the fate of their loved ones access to justice.

approach

Fady’s case is the first complaint brought to the UN Human Rights Committee regarding collective and summary expulsions from Greece—and one of a few brought against EU border violence. It is unique for arguing that Fady’s abduction, deprivation of liberty, and illegal expulsion constitute an act of enforced disappearance under international law.

Unlike the European Court of Human Rights, which has been the main forum for cases of ‘pushbacks’ at the EU’s borders (see also, Aegean ‘driftbacks’ before the ECtHR), the Human Rights Committee can offer ‘general remedies’ regarding the systemic practices of ‘pushbacks’, beyond the specific reparative measures in Fady’s case. These include (para. 84 of the complaint): recognition, reforms and accountability for systemic practice of ‘pushbacks’; transparency regarding border enforcement activities, and evidence collection; and consideration of the obligations of third parties including EU institutions.

Since its filing, Fady’s case has been included in submissions made by civil society organisations in the context of Greece’s first review by the Committee on Enforced Disappearances, whose 2022 Concluding Observations on Greece condemn its violations of the Convention resulting from its systemic practice of ‘pushbacks’. The factual patterns and legal arguments put forward in this case were also included in our submissions to the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances in the context of its elaboration of General Comment 1 on enforced disappearances in the migration context (adopted in September 2023).

Fady’s brother Mhamed remains missing to this day. Over the last several years, we have accompanied Fady in his search for Mhamed, including in filing a missing person claim to the German Red Cross. We have been unable to obtain any information relevant to his brother’s whereabouts or fate, and we have faced and exposed a multitude of obstacles. Fady’s case is part of a broader intervention and project on Enforced Disappearances, Necro-Violence, and Posthumous Struggles for Justice in Europe’s Borderlands.

developments

17 November 2020: Communication filed as F.A.J. v Greece with UN Petitions (while the legal team were part of the Global Legal Action Network (GLAN))

5 November 2021: Communication registered by the Committee as F.A.A. v Greece (CCPR 4038/2021) and communicated by the Committee to Greece

27 October 2022: State party’s observations on the admissibility and merits, dated 5 May 2021, and Third Party Intervention (TPI) by the Border Violence Monitoring Network (BVMN), dated 27 June 2022, sent to us by Petitions

27 February 2023: Our comments on the Greek Government’s observations and on BVMN’s TPI sent to Petitions

3 March 2023: State party’s observations on the BVMN TPI, dated 23 December 2022, sent to us by Petitions

11 September 2023: TPI by Paris Human Rights Center (CRDH) and the Assas International Law Clinic at Université Paris II – Panthéon Assas sent to us by Petitions

13 November 2023: Our comments on the CRDH TPI sent to Petitions

14 November 2023: Communication 4038/2021 considered ‘procedurally ready’ for examination by the Committee, to be scheduled for its upcoming sessions

research

Valentina Azarova, ‘Enforced Disappearance, Necro-Violence and Posthumous Politics in the Borderlands: From the Sonoran Desert to Evros’, Badacze i badaczki na granicy / Researchers on the Border, Research Seminar at Polish-Belarus Border, 21-23 April 2023

Valentina Azarova, Amanda Brown and Itamar Mann, The Enforced Disappearance of Migrants, Boston University Journal of International Law 40:1 (2022) 133-204

Valentina Azarova, Amanda Brown and Itamar Mann, ‘Forced Disappearances: From Authoritarianism to Border Violence’, Fortress (North) America, Boston University School of Law, 12-13 March 2021

Valentina Azarova, ‘The Production of Enforced Disappearances in the Evros/Meriç Borderlands’, 7th Expert Seminar on Enforced Disappearances, organised by Geneva for Human Rights and the missions of Argentina, Chile, France and The Netherlands, 24 November 2021

Valentina Azarova, Amanda Brown, Charles Heller, Niamh Keady-Tabbal, Noemi Magugliani, Itamar Mann, Violeta Moreno-Lax, Lorenzo Pezzani, Documenting and litigating against the shifting practices of refoulement across the EU’s maritime frontier, Asyl 3 (2021) 13-17

media and related publications

John Washington, “I didn’t exist”: A Syrian Asylum-Seeker’s Case Reframes Migrant Abuses as Enforced Disappearances, The Intercept, 28 February 2021

Katy Fallon, Greece faces legal action over alleged expulsion of Syrian to Turkey, The Guardian, 17 November 2020

latest updates

-

Transforming justice for border deaths and disappearances: Call for expressions of interest

As de:border // migration justice collective and Missing Migrants Lesvos, we have been weaving the initial constellations of a transnational group of individuals, many part of groups or organisations, that have sought to respond to and resist border deaths and disappearances. We are now inviting expressions of interest to join an embodied co-learning…

-

Joint submission to the UN Special Rapporteur on Migrants on the ‘phenomenon’ of missing migrants

On 13 December 2024, de:border // migration justice collective and Legal Centre Lesvos provided their joint input to the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants’ report on the ‘phenomenon’ of ‘missing’ migrants. The joint submission discusses the underlying causes of migrants’ disappearances during border crossings and the…

-

European Ombudsperson opens inquiry into the Commission’s administration of EU funding used in Greece’s illegal expulsion of migrants

The inquiry is based on the joint submission of a complaint against the European Commission by de:border // migration justice collective, Legal Centre Lesvos, HIAS Greece, Equal Rights Beyond Borders, and Mobile Info Team, with the support of several investigative and research partners—including Dr. Lena Karamanidou, Border Violence Monitoring Network, Forensic Architecture and Lighthouse Reports.

Valentina Azarova

Amanda Danson Brown

Anan Abu Shanab

Partners

Forensic Architecture

Contributors

HumanRights360

Case documents

Redacted complaint

Third Party Intervention submitted by Border Violence Monitoring Network

Related submissions

Comments on the Committee on Enforced Disappearances draft General Comment 1 on Enforced Disappearances in the Context of Migration, submitted by de:border and Legal Centre Lesvos on 15 June 2023

Initial Comments in View of the Committee on Enforced Disappearances’ Elaboration of a New General Comment on Enforced Disappearances in the Migration Context, submitted by de:border on 20 June 2022

Border Violence Monitoring Network, Info from Civil Society Organizations for Greece’s reporting to the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances, March 2022

Noemi Magugliani, Niamh Keady-Tabbal, Róisín Dunbar and Amanda Brown, ‘Submission to the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants’ report on pushback practices and their impact on the human rights of migrants’ (2021)

Last updated

May 2024